Summer is still sizzling, but fall is around the corner, and what comes with autumn? That’s right, school. Many students will be starting up their science classes, whether they’re high school or college level. And that means that they will be exposed to potential hazards while doing their work and (we hope) earning their “A”s. Do they know how to protect themselves?

Certainly, when I was in school, we didn’t learn much about safety in the lab. Spills, fires, and the occasional chemical injury were not uncommon. For example, I was plagued once by a nasty, blistery rash that doctors couldn’t explain – until they realized I was handling a chemical in the lab that was closely related to the active ingredient of poison ivy.

Today, though, there are many resources to help students stay safe. Of course, the first should be the school itself. Students should always be briefed on how to conduct their experiments safely. But with a little extra instruction, they can take their own steps to find out about safety in the lab. And remember, this will possibly create good habits if they end up working with chemicals after graduation.

First – Identify the Hazards

All people who work with chemicals (in workplace, educational, or home settings) should know how to read a product label. In the lab, most products will have WHMIS (Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System) labels if in Canada or OSHA (Occupational Health and Safety Act) labels if in the United States. (Note that there may be slight differences between the label requirements for laboratory chemicals versus industrial ones). The requirements are based on the Globally Harmonized System for Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) developed by the United Nations.

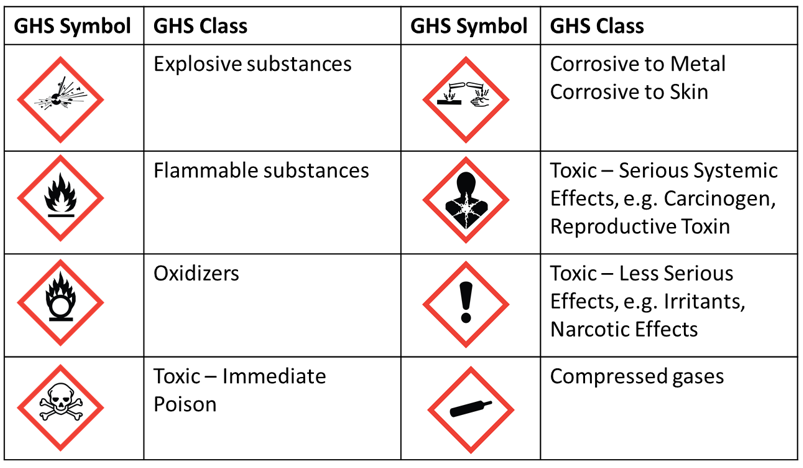

There are eight major symbols that can be found in the WHMIS/OSHA system, and they can be quickly learned by students. Look for the pattern of a red diamond with a black symbol inside.

However, other products in the lab may not be primarily intended for workplace sale. Many are intended as consumer products. These will have different symbols, but the symbols should still be recognizable by the general public (for example, skull and crossbones for toxic products and flame symbols for flammable material.) Perhaps you can practice by having a scavenger hunt around the house to find products with consumer labels on them, such as bleach or aerosol sprays.

Whether the product has a workplace label or a consumer one, the label on each container of hazardous product should include the name (“identifier”) of the product, a summary of its hazards, and instructions for safe use. Make it a habit to read the label on each product you use in the lab as well as at home.

In addition to the label, more detailed information should be available on the Safety Data Sheet (SDS). These are required for hazardous workplace products and are usually provided (although they are optional) on consumer products. If the teacher or professor doesn’t start by telling you where to find the SDSs in the lab, make sure to ask. These will have a summary of the hazards, a detailed breakdown of the ingredients, more detailed information on hazards, and information on how to handle the product safely and respond to emergencies. A vital piece of information should be in the first section – the 24-hour emergency telephone number. If you need guidance from a live person, you can call this number for more assistance.

Next – Protect Your Body

In Section 8 of the SDS, you’ll see the manufacturer’s suggestions for “individual protective measures,” which include Personal Protective Equipment, or PPE. This information should be reviewed taking into consideration things like the quantity of product you’ll be using and how well ventilated the lab is. But don’t assume that you can’t get hurt using things the school requires you to use!

Typically, the SDS may recommend PPE such as:

- Gloves – not all gloves are created equal. Some glove materials may be more resistant to corrosives, while others are best at protecting against solvents. If you’re allergic to certain glove materials, let your instructor know. Replace any torn or damaged gloves immediately.

- Eye protection – this is vitally important when working with corrosives such as acids or alkalies, but let’s face it, no chemical is going to feel good if it gets in your eyes. Note that if you find your school only provides basic quality glasses or goggles that might not fit your face well, see if your instructor will allow you to provide your own. Safety supply stores stock many cost-effective goggles that have better-quality lenses. and can help with situations such as finding a pair that will work over your normal glasses without being too heavy.

- Respiratory protection – unless your instructor sees a specific need, you probably won’t have to work with chemicals that require a respirator to protect your lungs. Usually, a well-ventilated room is enough protection for high-school experiments. In college, where you may be working with more toxic chemicals, most such experiments should be carried out in enclosures such as “fume hoods” to keep the chemicals out of the breathing zone. (Make sure they’re working – I spent several days working with cyanides in a fume hood only to discover the wiring had failed and it was providing no suction at all!)

- Body protection – the classic “lab coat” may look dorky, but it’s used by scientists for a reason. It keeps you safe in chemical spills, protecting not only your skin but your clothing. Did you know nitric acid spray dissolves acrylic yarn? I didn’t, until an accident with a few drops of the stuff left me with the Case of the Disappearing Pants. Very embarrassing.

Prepare for Emergencies

Once you know what sort of hazards you’ll be facing in the lab, do a quick survey of how to respond if something does go wrong.

- Fires aren’t uncommon in labs involving flammable chemicals. Note where the fire extinguishers are located in your lab. Ask your instructor if you have fire blankets, and learn how to use one if a fellow student is on fire. And review the steps to follow if you catch on fire yourself. “Stop, drop and roll” is an important rule – running in a panic only provides extra oxygen to a fire. If you’re working in an advanced lab, you may need different extinguishers for different types of fires – check each one out, and know how to use it. If your instructor hasn’t arranged it already, ask if you can have someone from your safety group or the fire department give a demonstration on how to use extinguishers properly, because they’re not always easy to figure out in an emergency.

- Check the SDS or a basic first aid guide for instructions on poisoning. Unfortunately, what we see in movies is often wrong. In most cases, don’t try to make the victim throw up. Call 911 or your assigned emergency number, and get the person to professional aid as soon as possible. If they’re starting to vomit already, have them lie on their left side, mouth down, so they don’t choke.

- Corrosives on the skin (or worse, in the eyes) require immediate action. A well-designed lab should have an eye-wash station and a safety shower. If not, use whatever water sources are available. Keep rinsing while someone calls 911 or your emergency number. Eye exposure to chemicals should always be checked out by a medical professional.

Chemical Hygiene Steps

Remember the scene from “Dr Strange” when he discovers the warnings come after the spells? Sometimes experiments are like that. Read through your procedure fully before trying it out.

Some other important things to remember:

- Keep your work area clear of unnecessary clutter.

- Keep yourself clear of unnecessary clutter. Keep long hair tied back, and remove any jewelry that might be exposed. This protects the jewelry, but also your skin. I still have a scar from where a chemical ran under my watch and burned the skin.

- Put containers of chemicals away after using them. A good approach is to measure out what you need into a beaker or dish and put larger containers away during the experiment.

- Know how to use equipment before starting.

- Clean up spills as soon as they occur.

- Find out in advance where used chemicals should be disposed of. Many chemicals can’t simply be poured down the drain. They can harm the environment or even react dangerously.

- If you want to extend your experiment by doing something not in the procedure, ask your instructor. They may say no, but they may also say yes, and give you guidance on how to do it safely.

- Don’t eat or drink while working with chemicals. And don’t, whatever you do, put chemicals into something that looks like it contains food or drink.

- Obviously, no rough-housing, mixing unknown chemical combinations or practical jokes involving chemicals in the lab. But you knew that, didn’t you?

- Remember the rule that I took several tries to memorize – “hot glass looks just like cool glass.”

- If anything goes wrong – a spill, fire or exposure – tell your instructor right away. Chemical problems usually don’t go away if you ignore them long enough.

- Clean your workstation thoroughly at the end of the experiment. Make sure any gas jets are closed fully and all electrical equipment is turned off (unplugged if feasible).

- Wash your hands thoroughly after working with chemicals. Launder your clothes before re-wearing them, just in case you’ve spilled something on them you didn’t notice.

As a student (or parent of a student), there are many resources online or at your library for learning about chemical safety. But don’t hesitate to talk to your school administrator, teacher or lab instructor if you have any questions. Never assume that just because your school or university allows you to handle a chemical, it must be safe from harm. Protect yourself with the knowledge provided by the school and chemical suppliers.

Of course, if you have any questions about chemical safety or how the health and safety regulations apply to educational settings, call us here at ICC (888-442-9628 for our U.S. offices, 888-977-4834 for our Canadian offices) and we’ll help you figure out what the requirements are.

Sources:

American Chemical Society, Guidelines for Chemical Safety in Secondary Schools, https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/about/governance/committees/chemicalsafety/publications/acs-secondary-safety-guidelines.pdf

U.S. Consumer Safety Product Commission, School Chemistry Laboratory Safety Guide, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2007-107/pdfs/2007-107.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education, School Administration – Health and Safety, http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/workplace.html

University of Toronto, Chemical and Lab Safety, https://ehs.utoronto.ca/our-services/chemical-and-lab-safety/

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, First Aid for Chemical Exposures, https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/chemicals/firstaid.html

Stay up to date and sign up for our newsletter!

We have all the products, services and training you need to ensure your staff is properly trained and informed.

|

|

GHS (Workplace) Posters & Charts |

ICC USA

ICC USA ICC Canada

ICC Canada